25th March 2017

Standards Schmandards

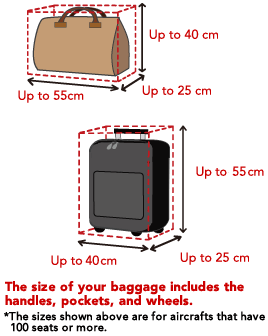

Last week I was waiting in line to board a flight and the passenger in front of me had a rather large carry-on bag that was clearly bigger than that depicted by the airline’s carry-on luggage sizing frame next to the gate. The passenger was told that his bag didn’t meet the standard for carry-on luggage and that he would have to check his bag. And that’s when the shouting started. “Standards? Schmandards! I take this flight every other week and always carry this bag on your plane. This is not the time to start telling me I can’t take it.” And on, and on, it went.

Now, I have no reason to doubt this gentleman was a regular flyer or, that he had used this bag on many a flight with this airline. Likewise the airline’s carry-on luggage standard was there for all to see. So why the commotion? Maybe this was a full flight, or maybe it was a smaller plane than usual. Whatever the reason, on this particular flight the airline decided to enforce its standard. It struck me that the underlying reason for the gentleman’s frustration was not so much the luggage standard, it was that he was the victim of a standard applied inconsistently.

What?

This incident raised all sorts of questions. The airline has a published standard for luggage. When we purchase our tickets we have to check a box acknowledging all the terms and conditions of flying. Then, the sizing frames at all the airport gates that say your bag has to be “this big to fly” are constant reminders that a standard exists. Yet many people flaunt the standard, “it’ll fit” they say. What is the standard then? Is it “take whatever you like but we reserve the right to call you on it when it suits us”? Is it the passenger’s responsibility to abide by the standard, even if they see fellow travellers ignoring it?

So What?

This interaction made me think about the application of standards at work. We have performance standards, process standards, behavioural standards, standards based on organisational values and standards around culture. Some are written down, some are in policies and rule books, some are on the walls in the form of skilfully designed posters, and some, well, we just figure them out as we go along.

BUT. Does your organisation apply all your standards consistently? Do you have so many standards that employees can’t keep track of what is most important? If so, does your organisation run a risk that inconsistent application will cause frustration, or even disengagement among employees?

A standard comes from the notion of “taking a stand”, and we generally only do this on matters of high importance, and so it follows that we really should only create standards where they are vitally important.

It’s a given that it is the role of the leadership to define the purpose of the organisation and to a large extent we see evidence of that when we work with leadership teams. However, what we see less of is evidence of a regular dialogue among leadership of the most important standards for the organisation in terms of performance and behaviour and, perhaps more importantly, the dialogue on the performance or behaviour they will accept with regard to each standard.

This dialogue on the standard you will accept is not easy, as the leaders have to agree on what tolerance exists around the standard and, under what circumstances would a breach of, or variance from, the standards be acceptable. Invariably, opinions in the leadership team will be mixed. But if the leadership team can’t agree, how are employees expected to follow?

Now What?

If you are clear on the purpose of your organisation then it may be worth clarifying the standards you will accept in three or four areas of performance and behaviour; the “what” and “how” of performance. For example:

- Revenue budgets are real; a 0.25% shortfall is a miss, not something to be rounded upwards

- Profit is a vital ingredient for any business and every cost has a consequence on this

- Any act of theft has consequences; lower materiality doesn’t change the act

- Every staff member deserves a fair hearing and natural justice

- No-one is exempt from cost-cutting if it’s needed; especially not the executives

- Any and all customer complaints are valid and need to be responded to

- Any form of harassment or bullying is unacceptable, regardless of provocation

The key to a good standard is clear, precise language. For example, one CEO we know created a clear standard on performance within his leadership team that “you are responsible for your objectives and outcomes and I won’t interfere in your day to day operations. However I need to be informed the moment you believe you won’t meet them.”

Once you’re on purpose, and have established standards on key areas of performance and behaviour (defining what is acceptable and what is not), there are two final steps to making this work. The first is to be clear on how you will manage against the standards; in other words how you will respond to over, or under performance. Will people be given a grace period? Are the standards guidelines, or will you enforce them every time?

The second step is to regularly assess the impact of managing against the standards. Is engagement increasing because people are clear about what’s expected of them and rewards and consequences are clear for high and low performance? Or, are people leaving because the delivery is too tough, or too inconsistent or indeed, too low?

In Summary

Being clear to everyone on the standards you accept is a vital part of what it means to be a leader. While it starts with the peak leadership team of the organisation, these same principles apply to each and every leader in the organisation. And, the more leaders you have in your organisation who do this, the less you have to worry about reverting to rule books and policy manuals and colourful posters to adorn the walls, and the more you can focus on the real work of the organisation.

Once leaders have come to an agreement on standards and how you plan to measure against these standards, the next natural step is to communicate these standards to the broader teams and ensure employee roles and responsibilities align with them. To help facilitate a healthy discussion around this, we recommend using our One Page Job Description Template, which you can download here.

Categories: Developing Leaders